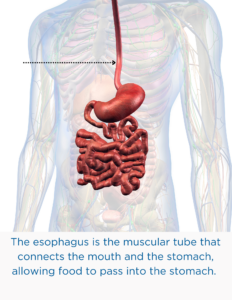

Gastroesophageal reflux is the backflow of stomach contents into the esophagus. Under normal circumstances, the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) acts like a valve to prevent backflow.

During the first year, “spitting up” is a normal phenomena in infants. It generally takes about a year for the LES to mature. If reflux persists beyond the first year, it can lead to a failure to gain weight adequately, irritation of the esophagus, and aspiration with respiratory difficulties.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) refers to symptoms or tissue damage caused by gastroesophageal reflux.

If you suspect your child may be suffering from reflux, the first step is to consult a physician and obtain an accurate diagnosis. The diagnosis of GERD can often be made based upon symptoms and may be confirmed by one or more tests.

Gastroesophageal reflux-associated lung disease

Several groups of children are at risk for gastroesophageal reflux-associated lung disease.

In some children with asthma, symptoms are caused in part by gastroesophageal reflux. Minute amounts of material from the stomach which come back up into the throat may be inhaled into the lungs (aspiration). Sometimes acid in the esophagus may stimulate nerves that cause wheezing.

Children with cystic fibrosis often suffer from heartburn.

Pre-term infants who develop bronchopulmonary dysplasia [abnormal development of the lungs and their air passages], the chronic lung disease of the newborn, may have gastroesophageal reflux adding to their problems.

Children with nerve or muscle disorders disturbing their swallowing are at risk for pneumonia that comes from refluxed material going down the trachea into the lungs.

Children who have had successful surgery to repair a congenital blind end to the esophagus (esophageal atresia) are also at risk.

All these conditions often benefit from treatment for gastroesophageal reflux.

Tests to Confirm a Diagnosis of GERD

The diagnosis of GERD may be confirmed by one or more tests. Often, the first test performed is a barium swallow and upper gastrointestinal x-ray series to assess for structural problems such as

- hiatal hernia- a small opening in the diaphragm that allows the upper part of the stomach to move up into the chest

- pyloric stenosis- a narrowing of the opening between the stomach and the small intestine

- malrotation- twisting of the intestine that may result in obstruction

The child must drink a chalky substance called barium, which shows up white on the x-ray.

The most important reason for doing a barium swallow is to make sure there is normal anatomy, and not a hiatal hernia or some other anatomic cause predisposing to gastroesophageal reflux. However, the barium study is a poor test for reflux itself. In children with a hiatal hernia, the top of the stomach moves through a hole in the diaphragm into the chest. A hiatal hernia is not synonymous with gastroesophageal reflux disease, but may be a contributing factor.

Gastroesophageal reflux may cause pulmonary complications. Prolonged intraesophageal pH monitoring may document that incidents of reflux immediately precede breathing difficulties, wheezing, or coughing episodes. To do this study, a thin plastic tube is passed through a nostril and into the esophagus. It is taped securely to the nose, and attached to a portable recording device. After a day of recording, the results are analyzed. Since everybody has some reflux, often it is especially important to record the child’s symptoms and activities in a diary, so that associations can be made between the episodes of reflux and the symptom.

Scintiscans (milk scans) over the lungs may detect aspiration. The child drinks formula with a tiny, harmless amount of radioactivity in it. Then the child must lie quietly on a hard table under a large metal disc that is a camera which measures the movement of the radioactivity.

If the child is inhaling formula, radioactivity shows up in the lungs. Neither pH monitoring nor scintiscanning is very sensitive for proving that reflux is causing lung problems, but they are worthwhile studies in some children with persistent symptoms. Most often when gastroesophageal reflux is considered to be involved in the development of pulmonary disease, a treatment trial is warranted, even if tests are unrevealing.

The best diagnostic test for esophagitis is the esophageal biopsy, which is often accomplished at the time of an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. For endoscopy, the child is sedated, and a flexible plastic tube with a tiny camera on the end is inserted through the mouth, down the throat, and into the esophagus and stomach.

During this test, which takes about 15 minutes to do (but several hours for preparation and recovery), the esophageal and stomach walls are carefully inspected for signs of inflammation. Biopsies are pinhead-sized pieces of the surface tissue layer. They are inspected under the microscope.

Results from the endoscopy are immediate: hiatal hernias, ulcers, and inflammation are readily identified. Precise diagnoses sometimes require the biopsy results, which are complete a day or two after the endoscopy.

Sometimes it is necessary to evaluate the possibility that gastroesophageal reflux disease is a consequence of a more generalized problem with the strength or coordination of the contractions which help to move food through the digestive system.

A gastric emptying study measures the time it takes for food to leave the stomach. It is a useful screening test, especially when the results are normal. It is the same test as a milk scan, but measurements are focused on the speed by which a meal leaves the stomach instead of detecting refluxed material in the lungs. (Both aspects can be measured simultaneously if need be.)

Many children find this test bothersome because they must be still under a camera for minutes at a time. Therefore, mildly abnormal results must be interpreted cautiously in infants and toddlers, because anger, excitement, and fear may delay gastric emptying.

Read personal stories other patients with GERD

🎬 Watch Now

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) – Pediatric

Dr Rachel Rosen is the Attending Physician, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition; Director, Aerodigestive Center at Boston Children’s Hospital and Associate Professor of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School.

In this video, she talks about why diagnosing GERD in infants is so vital, how to recognize nonacid reflux, treatment options currently available for children, and nutritional strategies to help patients manage reflux in infants.

Adapted from IFFGD Publication: Gastroesophageal Reflux in Infants and Children by Carlo Di Lorenzo, MD, Mark S. Glassman, MD, and Paul E. Hyman, MD.