What Does IBS Mean

Irritable bowel syndrome is a disturbance of bowel function that includes symptoms of abdominal pain or discomfort and altered bowel habit (change in frequency or consistency) – chronic or recurrent diarrhea, constipation, or both in alternation. IBS comprises a group of functional bowel disorders.

Irritable bowel syndrome is a disturbance of bowel function that includes symptoms of abdominal pain or discomfort and altered bowel habit (change in frequency or consistency) – chronic or recurrent diarrhea, constipation, or both in alternation. IBS comprises a group of functional bowel disorders.

“Irritable Bowel” refers to a disturbance in the regulation of bowel function that results in unusual nerve sensitivity and muscle activity.

“Syndrome” refers to a number of symptoms and not one symptom exclusively.

How Common is IBS

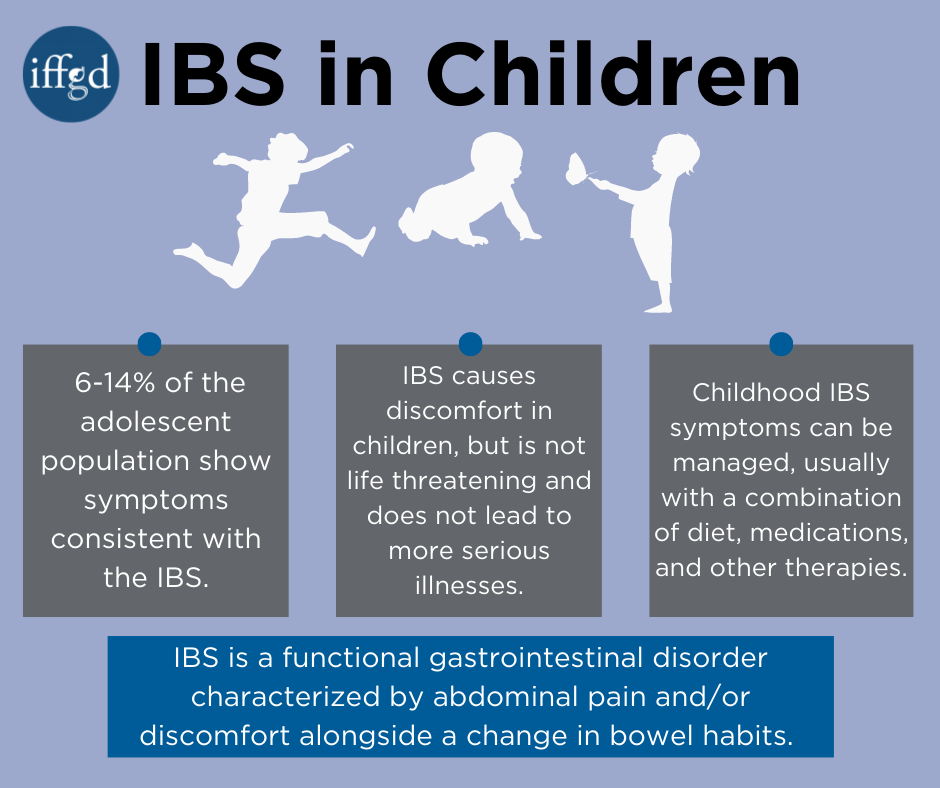

A population based study of 507 middle school and high school students by Hyams et al. indicated that 6-14% of the adolescent population note symptoms consistent with the IBS. In the study, anxiety and depression scores were significantly higher for students with IBS-type symptoms compared with those without symptoms. Eight percent of all students had seen a physician for abdominal pain in the previous year. These visits were correlated with abdominal pain severity, frequency, duration, and disruption of normal activities; they were not correlated with anxiety, depression, gender, family structure, or ethnicity.

What Are The Symptoms of IBS

The symptoms of IBS include abdominal pain or discomfort and changes in bowel habits. To meet the definition of IBS, the pain or discomfort should be associated with two of the following three symptoms:

- start with bowel movements that occur more or less often than usual

- start with stool that appears looser and more watery or harder and more lumpy than usual

- improve with a bowel movement

Other symptoms of IBS may include

- diarrhea – having loose, watery stools three or more times a day and feeling urgency to have a bowel movement

- constipation – having hard, dry stools; two or fewer bowel movements in a week; or straining to have a bowel movement

- feeling that a bowel movement is incomplete

- passing mucus, a clear liquid made by the intestines that coats and protects tissues in the GI tract

- abdominal bloating

Symptoms may often occur after eating a meal. To meet the definition of IBS, symptoms must occur at least once per week for at least 2 months.

Diagnostic Criteria (Rome III) – children and adolescents aged 4 to 18**

Criteria fulfilled at least once per week for at least 2 months prior to diagnosis. Must include both of the following:

- Abdominal discomfort* or pain that has two out of three features:

-

Improvement with defecation; and/or

-

Onset associated with a change in frequency of stool; and/or

-

Onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool.

- No evidence of an inflammatory, anatomic, metabolic, or neoplastic process that explains the subject’s symptoms.

*”Discomfort” means an uncomfortable sensation not described as pain.

** The diagnostic criteria for IBS are applied after the child becomes a reliable reporter for pain, typically in the early school years.

Children with IBS may also have headache, nausea, or mucus in the stool. Weight loss may occur if a child eats less to try to avoid pain.

How is IBS Diagnosed

Some Sugars Can Cause Diarrhea

The artificial sugar sorbitol is used as a sweetener. For example, it is often used to sweeten diet gums and candies. It has no calories, but is a known laxative if taken in sufficient amount. A glance at the ingredients of many confections or sweets will reveal the offending sugar. Mannitol is another sweet substance frequently found with sorbitol.

Fructose is a natural calorie-containing sugar found in fruit. It is one reason why large amounts of fruit can cause diarrhea. It is also naturally present in onions, artichokes, and wheat. It is also used as a sweetener and may be found in candies, soft drinks and fruit drinks, honey, and preservatives; and in sufficient amounts can cause diarrhea.

A history that fits the Rome Criteria for a diagnosis of IBS, accompanied by a normal physical examination and normal growth history, are consistent with a diagnosis of childhood IBS. A nutritional history, assessing for adequacy of dietary fiber in those with constipation, as well as ingestion of sugars such as sorbitol and fructose in those with diarrhea, is often useful.

Factors alerting the clinician to the possibility of disease include night time (nocturnal) pain or diarrhea, weight loss, rectal bleeding, fever, arthritis, delayed puberty, and a family history of inflammatory bowel disease.

A limited laboratory screening for disease is frequently reassuring to the clinician, patient, and family for patients with persistent symptoms and may include a complete blood count, stool studies, and breath hydrogen testing or a trial of a milk free diet for lactose malabsorption.

Psychologic Features

The population based study by Hyams et al. noted that anxiety and depression were more prevalent in adolescents with IBS than the control population. However, psychological data in childhood are limited to assessments in recurrent abdominal pain, and so are not directly applicable to childhood irritable bowel syndrome.

Of Interest – Linaclotide Study for Treatment of IBS-C in Children

March 22, 2016 – Participants sought for a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled safety and efficacy study of a range of linaclotide doses administered orally to children ages 7 to 17 years, with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C). The purpose of this study is to evaluate the safety and efficacy of linaclotide for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C), in children ages 7-17 years. Learn more

Treatment

Once there is a diagnosis of IBS, the treatment goals are to provide effective reassurance to the child and family, and to reduce or eliminate the symptom(s). The doctor must educate and reassure the child and family that although IBS causes discomfort it does not lead to more serious disease and is not life-threatening.

While there is no cure for IBS the symptoms can usually be reducd. This often includes a combination of approaches including changes in diet, medications, and other therapies.

Large meals can cause cramping and diarrhea, so eating smaller meals more often, or eating smaller portions, may help IBS symptoms. Eating meals that are low in fat and high in carbohydrates, such as pasta, rice, whole-grain breads and cereals, fruits, and vegetables may help.

Certain foods and drinks may cause IBS symptoms in some children, such as

- foods high in fat

- milk products

- drinks with caffeine

- drinks with large amounts of artificial sweeteners, which are substances used in place of sugar

- foods that may cause gas, such as beans and cabbage

Children with IBS may want to limit or avoid these foods. Keeping a food diary is a good way to track which foods cause symptoms so they can be excluded from or reduced in the diet.

The presence or severity of the pain should not be disputed. A review of the current understanding of IBS and the effects that stress and anxiety can have on worsening the condition helps the child and family to understand why the pain occurs. Psychosocial difficulties and triggering events for symptoms will be asked about and, if present, addressed.

Children and Fiber

Children, as well as adults, benefit from a balance of fiber in their diet. Their requirements are less than for adults. For children, ages 3 to 18, the American Dietetic Association reports a formula for determining recommended fiber intake – a child’s age plus 5 equals the grams of dietary fiber he or she should eat daily. Good sources are fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. As with anyone increasing dietary fiber, it is important to drink extra liquids such as water, or milk.

Medications may be used – such as a tricyclic antidepressant, which in low doses acts as a pain reliever, or anticholinergics to help control intestinal cramping. However, effectiveness of these drugs in children is anecdotal and not supported by well-designed studies to confirm their efficacy. In those with constipation increased dietary fiber may be recommended. However, fiber is often associated with an increase in intestinal gas production, and may increase abdominal cramps and flatulence. Flatulence is especially embarrassing to the school-age child.

The following therapies can help improve IBS symptoms when emotional factors play a role:

- Talk therapy. Talking with a therapist may reduce stress and improve IBS symptoms. Two types of talk therapy used to treat IBS are cognitive behavioral therapy and psychodynamic, or interpersonal, therapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy focuses on the child’s thoughts and actions. Psychodynamic therapy focuses on how emotions affect IBS symptoms. This type of therapy often involves relaxation and stress management techniques.

- Hypnotherapy. In hypnotherapy, the therapist uses hypnosis to help the child relax into a trancelike state. This type of therapy may help the child relax the muscles in the colon.

In patients with symptoms that do not respond to treatment, endoscopic evaluation of the colon may be done. Irritable bowel syndrome may coexist with inflammatory bowel disease. Tests can differentiate an inflammatory bowel disease from a functional GI disorder such as IBS.

Sources

Drossman DA, et al. (Eds). Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders. In Rome III: The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Virginia: Degnon Assocs. Third Edition, 2006.

Hyams JS, Burke G, Davis PM, Rzepski B, Andrulonis PA. Abdominal pain and irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents: a community-based study. J Pediatr 1996 Aug;129(2):220-226.

Caplan A, Rasquin A. What’s new in pediatric functional gastrointestinal disorders. IFFGD Fact Sheet No. 824; 2002.

NIH Publication No. 12-4640. Irritable bowel syndrome in children. July 2012.